Before an observatory can plumb the secrets of the cosmos, it must navigate more humbling challenges.

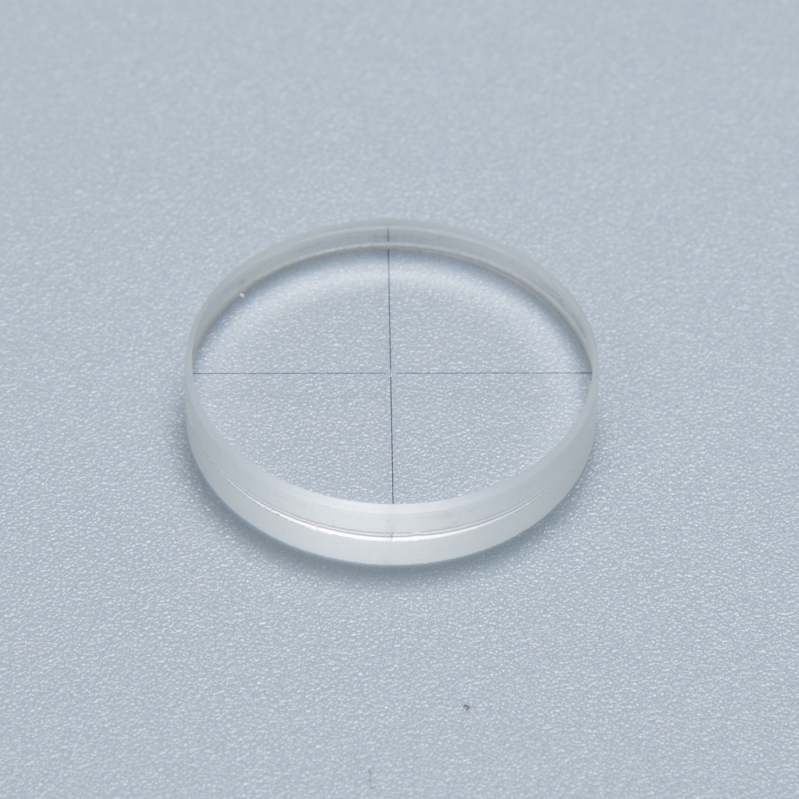

Few things in science appear to be as delicate or precarious as the giant mirrors at the hearts of modern telescopes. These mirrors — doughnuts of glass meters in diameter, weighing tons and costing millions of dollars — are polished within a fraction of a wavelength of visible light into the precise concavity required to gather and focus starlight from the other end of the universe. Reticels

When not at work, they are sheltered in lofty domes that protect them from the distortions of humidity, wind and changes in temperature. But this cannot shield them from all the vicissitudes of nature and humanity, as I was reminded on a recent visit to the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile.

As my hosts showed off one of their prized telescope mirrors — 20 feet of shiny, immaculately curved aluminum-coated glass — I couldn’t help noticing a small, suspicious smudge. It looked like the kind of smear you might find on your windshield in the morning, especially if you had parked under a tree.

“Birds,” one astronomer grumbled when asked what it was.

It happens all the time, other astronomers say. Michael Bolte, now an emeritus professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz, recalled giving the governor of Wyoming a tour of the Wyoming Infrared Observatory, outside Laramie, in 1981. “We went up on the service platform and looked down, and there were bird droppings all over the mirror,” he said. “It looked awful.”

It’s not only birds that can deface a mirror. Mike Brotherton, the current director of the Wyoming observatory, posted a picture on Facebook of frost that had accumulated on his mirror while the dome was open for observation. “It’s hard to keep a mirror pristine,” he said. “It’s a balance between opening to take data and protecting the mirror.”

Bird residue has a special place in astrophysical lore. In the early 1960s, the radio astronomers Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, both then at Bell Labs, were trying to calibrate an old horn antenna to study galaxies. In an effort to get rid of a persistent background hum, they shoveled vast amounts of pigeon guano out of their telescope, only to eventually learn that the hum was cosmic: It was the hissing remains of radiation from the Big Bang, and it firmly settled the question of whether the universe had a distinct beginning.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

We are confirming your access to this article, this will take just a moment. However, if you are using Reader mode please log in, subscribe, or exit Reader mode since we are unable to verify access in that state.

Concave Mirror Convex Mirror Concave Lens Convex Lens If you are a subscriber, please log in.